A few years back, while toying with a story I’d eventually abandon, I wrote a scene involving a bog and a blind girl and a will-o’-the-wisp light. It was one of the few scenes I missed when I decided to tuck that story into a drawer, and so I pulled elements out of it and into a completely new tale.

A blind girl. A bog. A ghost light.

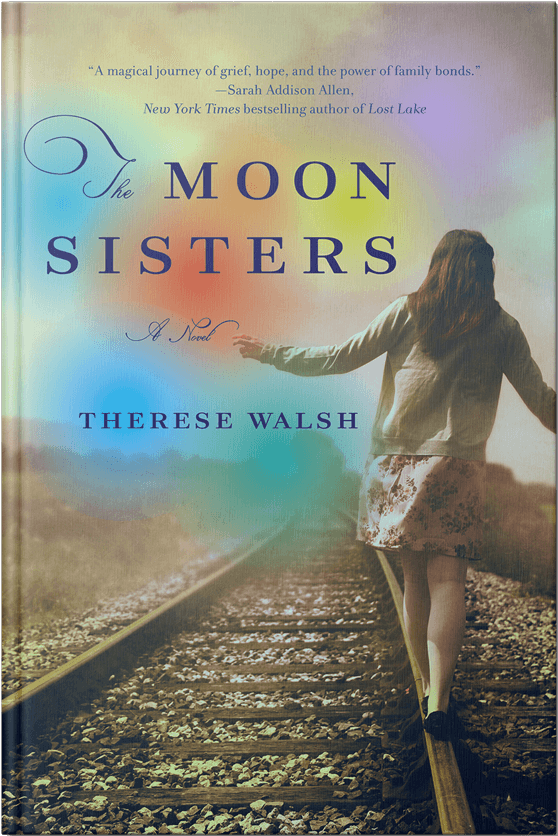

The Moon Sisters is the story of a young woman’s quest to find a will-o’-the-wisp light, because seeing one was her recently deceased mother’s unfulfilled dream. Also called “foolish fires,” these ghost lights are sometimes seen over wetlands and have a whole mythology of their own. They’re thought to lead those who follow to treasure, but they’re never captured and can sometimes result in injury and even death for adventurers. The metaphor of that fire—that some dreams and goals are impossible to reach, and that hope itself may not be innately good—eventually rooted its way into the tale as this young woman, Olivia Moon, and her sister, Jazz, try to come to terms with real-life dreams and hopes, and with each other, in their strange new world.

The story has a more personal meaning for me, too, as my father passed away when my youngest sister was still a teenager. Grappling with death and the very meaning of life has been something my two sisters and I have struggled with, individually and collectively, since that time.

I put an article about synesthesia into a story ideas folder many years ago. It seemed an intriguing topic to explore via fiction—this notion that sensory areas might intermingle in ways most of us don’t experience, so that a person might taste sounds or smell sights.

The character of Olivia Moon evolved out of the idea of synesthesia. I think in many ways her personality reflects some of the aspects of the condition itself: She is colorful, unique, spontaneous, and a big proponent of the idea that there are typically at least two ways to look at things.

Ultimately, both the condition and the character set the stage for one of the book’s big themes: altering perceptions. For example, when Olivia meets new people, she relies upon her synesthetic senses to take their measure. We see an important instance of this when Olivia meets a tattooed train hopper named Hobbs. Though Hobbs warns Olivia that he can’t be trusted, she relies on his voice—not only how he speaks and what he says, but the shape of his voice—to determine his reliability. When Jazz meets Hobbs, she makes a more stereotypical assumption based upon his appearance and decides that they need to stay away from him. Though Olivia and Jazz have very different points of view, they each separately come to question what they believe about Hobbs and many other things as the story unfolds.

A side note: Whenever I’m with a group of people and explain synesthesia, I usually find someone within that group who has it but was never aware of that fact. I find that fascinating! The question that usually elicits a gasp is, “Do you have a timeline in your mind, that you can summon up whenever you need it?” I spoke with a friend just the other day who said something like, “Wait, I have that. January sits squarely in the center of a curved line filled with dates.” This ability to summon up a sort of mental calendar is one of the most common forms of synesthesia.

In the early planning for The Moon Sisters, I knew Olivia would need someone’s help while on her journey. It was a natural leap to assume this person would be an older sibling—someone used to being in the “helper” role, whether they liked it or not. I may have considered a brother for Olivia for a full two seconds, but of course it had to be a sister. I know what it means to be a sister, and I understand the push-pull-love-hate blood bond that defines sisterhood; it’s a relationship dynamic with layers of conflict that can be rooted in childhood, and evolve and resolve over a lifetime.

Funny, but once I settled on the idea of a sister for Olivia, I didn’t fully develop that character until I met her on the page. Jazz appeared, chapter one, scene one, with an axe to grind, and I felt it. It was almost like she reached out of my computer to tell me, the author, “Hey, I’m extremely—extremely—important. Don’t mess it up.” (Except she wouldn’t have used the word “mess.”)

Since they each had a singular point of view, chapters alternate between their perspectives throughout the book. We not only see the distinctions in the way they process the world during their travels, and how each of them chooses or doesn’t choose to change over time, but we learn about the defining moments from their past. We come to understand quite a bit about their mother, Beth, too, as memories surface, and also through a slow reveal of old letters Beth wrote to her father. Life isn’t always a neat thing, and there’s a lack of resolution relating to those letters, which were never sent, and in the things the girls can’t go back and change about life with their mother—the things they said and didn’t say. That’s something they have to come to terms with, just as they have to come to terms with death itself in order to move on. With that in mind, I structured the story around the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

It wasn’t intentional, but there are some similarities between Olivia and Jazz and my actual sisters. My youngest sister is a wanderer like Olivia, and tends to be dreamy and spontaneous like her as well. My other sister is pragmatic and committed to her family, like Jazz, even when that family drives her crazy. (She’s also much more inclined to drop an “F bomb” than anyone I know!)

For a few reasons. Here’s a quick story: When I traveled to West Virginia in order to research this book, I took the time to talk with people when I could. One conversation stands out in my memory, which took place when I visited an exhibit on the history of music in Appalachia. The woman I spoke with, who was part of the organizational team for the event, seemed apprehensive when I first mentioned that I was writing a novel set in her state. As the conversation progressed, and she realized I wasn’t interested in propagating stereotypes about toothless hillbillies, she admitted how protective she and her fellow statesmen felt about their homeland and how they didn’t often open up to outsiders because of the cutting preconceived notions people have about West Virginia. It’s human nature. We erect barriers to defend ourselves.

That trip, and that conversation, confirmed for me that West Virginia was exactly the right setting for the book. I needed a location that felt a little wild, filled with bogs and swamplands and forests, where you might walk mile after mile without seeing another person. But beyond the suitability and beauty of its landscape, the setting of West Virginia supported the themes of perception and self-protection via defense mechanisms in The Moon Sisters.

Quite a bit. While I was in West Virginia, I explored the Cranberry Glades, interviewed a member of the West Virginia Department of Transportation’s State Rail Authority, and road a train with the president of the Durbin and Greenbrier Valley Railroad. I referenced railway maps, read books on train hopping and underground magazines on the train-hopper lifestyle, and even interviewed a train hopper. I interviewed a leading synesthesia researcher, haunted a synesthesia listserv, and read several books about the subject. I spoke with eye doctors to better understand the experience of a legally blind character. I read about being part of a family who loses a loved one to suicide. I also read books about a variety of quirky subjects, like recipes based on foods that grow wild in West Virginia, and songs about the great outdoors. I spent time reading some poetry written by West Virginians, too.

Writer Unboxed is a big part of my life; I manage the site, which has been around since 2006, and I help to oversee a Facebook community of over 5,000 writers. And though it might be said that it affects my writing life the most in terms of the time required for its upkeep, it’s more relevant to say that the people involved with Writer Unboxed inspire me continually—not just via the daily essays on the blog, but through the stories of struggles and triumphs that come through our Facebook group. The writing life can be a lonely one, but a true community of writers makes it anything but solitary.

I’d always heard that the second book is the hardest to write, and I hate to be typical but I did find that the five-year journey to complete The Moon Sisters took more out of me than my debut, which I worked on for six years. I honestly think knowledge of the book industry had quite a lot to do with that for me. When you’re writing a first book, you may know something about the industry, but you’re on the outside of it and so you have a certain amount of (blissful) ignorance. The second book is written with a full awareness of the industry—its expectations and realities, for better and worse. In a perfect world, the creative and business sides of a writer’s life would be separated, but that’s not easily done once you’ve been published.

All of that aside, I have a fierce love for The Moon Sisters—a greater love for it than for my debut, probably in part because of the challenge I felt in writing it. It stretched me as an author, and helped to prove something to myself about perseverance and commitment in difficult times. If I never pen another book, I’ll be glad that I finished this one; it’s the truest thing I’ve ever written.