Moira and Maeve huddled under the covers with Jane Eyre cracked open between them. Moira turned to her favorite section, where Mr. Rochester first asks Jane to marry him. “Listen to what he says to Jane here,” she said. “‘I sometimes have a queer feeling with regard to you—especially when you are near me, as now: it is as if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string situated in the corresponding quarter of your little frame. And if that boisterous Channel, and two hundred miles or so of land come broad between us, I am afraid that cord of communion will be snapt; and then I’ve a nervous notion I should take to bleeding inwardly. As for you,—you’d forget me.’”

“I would never forget you!” Maeve said.

“That’s what Jane says, too!”

Maeve giggled.

“Girls,” said Abby. “Close the book. It’s time for bed.”

Maeve put her mouth close to Moira’s ear. “We are joined that way,” she said. “Don’t you feel the string? Never snap it.”

“No more talking,” said Abby. “Go. To. Sleep.”

Moira closed her eyes and thought she felt something very like a string, very near her rib. She would not snap it. Not ever.

[End of excerpt]

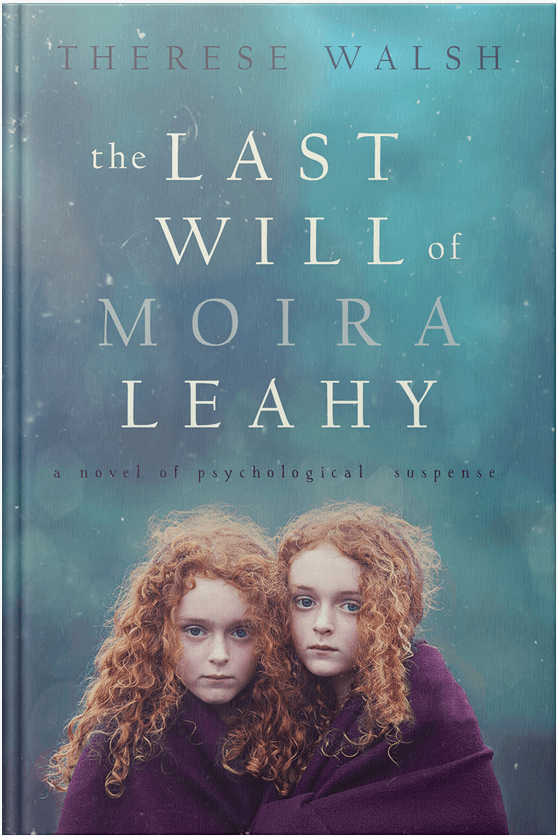

I could probably fill three books with all of the deleted text lying about due to this novel. Once I’d settled on writing The Last Will of Moira Leahy as women’s fiction, the only section of the book that didn’t give me trouble was the last; it was always clear what would happen in that section, and writing it was a simple, fluid experience.

The middle, not so easy.

And the beginning was a surprising challenge, in part because I was absolutely convinced that I’d need a prologue. Though I knew that nine of out ten people do not read prologues, I thought my prologue would become the special shiny one that everyone would admire. Writers’ egos are funny things.

Here are a few of the first paragraphs I drafted before settling on the winning graph, which I’ll post at the end.

TAKE ONE: Let’s try a clever prologue here called “Afterward.” First person. Tell them how important this story is. Go.

Lives are saved every day—great lives, the lives of children and animals and corrupt politicians and masses of people lucky enough to be forewarned of natural disasters. So I’ll give it to you: The story of a single saved life isn’t remarkable on the surface of things. But how this one life was saved is unique, and I don’t say that solely because it’s mine.

TAKE TWO: Try it in 3rd person, Jack Leahy’s point of view. Maeve and Moira are newborns. Go.

Finally his babies were here—both of them. Jack Leahy held out his arms awkwardly for the nurse, then all at once the first of his daughters was in them, a warm presence though hardly a weight. A great gladness bloomed in his chest as he studied her face—the ruddy cheeks, the lips that seemed to want to pout or purse, the eyes squinting open at him just a bit. He edged a careful finger toward her wee cap and nudged it to reveal a mop of red hair. The girl’s eyes opened wide at his laugh.

TAKE THREE: Make it moody. Maeve’s point of view. Indicate a little of what she’s lost. Go.

I used to love storms. Love them. I would sit before open doors and windows with Moira and my father through thunderstorms like this one, rain splattering at me through the screen, and be in awe of nature, of all its might and music. But that was Before.

TAKE FOUR: Speak to Abby’s discomfort with all things twin.

Abby Leahy was not the kind of mother to dress her twin girls in matching outfits; in fact, she did all she could to encourage individuality. She strove to spend time alone with her daughters daily even when they resisted these efforts, clinging to one another, speaking in their strange language, and giggling behind their hands.

TAKE FIVE: Same idea, but make it more subtle. Moira’s point of view. Go.

Moira thought it was seeing the conjoined boys at the twins convention that sent her mother over the edge.

TAKE SIX: In the name of Godiva, forget about the prologue ideas already! Get to the scene you know kicks things off—the auction scene. Maeve’s point of view. Go.

It was the middle of November, positively frigid out, and I’d left my lap-warming cat and a towering stack of papers to go to Lansing’s Block. I didn’t really know why, but that I was desperate to evade responsibility for an hour, and what else was there to do in a sleepy upstate New York town on a Sunday evening? Pathetic, I know, but I also felt I’d be a little less lonely among the strangers.

TAKE SEVEN: Lucky seven, please work. Less clinical. Get to the heart of the matter.

I lost my twin to a harsh November nine years ago. Ever since, I’ve felt the span of that month like no other, as if each of the calendar’s perfect little squares split in two on the page. I wished they’d just disappear. Bring on winter. I had bags of rock salt, a shovel, and a strong back. I wasn’t afraid of ice and snow. November always lingered, though, crackling under the foot of my memory like dead leaves.

Seven was, indeed, my lucky number.